Sam Houston’s Last Stand: Part 1

Note: This story is about a 48-hour period of uncertainty in Austin at the start of the Civil War. I am sharing it in two parts. This isn’t friggin’ LOST, or something, so if you genuinely do not know what happened, don’t Google it, because that’s like the previews giving away the ending of a movie. Okay: Enjoy.

A hush came over the audience, and the proceedings began with a prayer. For the men in that room, it was not an ordinary date. Eleven long days had passed, and men from all over Texas had come before the convention to take an oath: An oath to Texas and the Confederate States of America. Secession had passed as a resolution only weeks earlier.

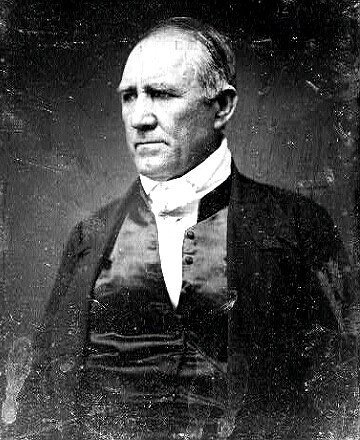

This day, March 16th, 1861, was Governor Sam Houston’s turn. Houston had spent the previous two months in bitter defiance of the threat of secession, but his feelings had softened some in the preceding weeks. He had often confided to personal friends that he could not turn his back on Texas.

Austin, after all, was a peculiar place for Governor Houston. Just two decades prior, Sam Houston had tried to literally steal the capitol from Austin by moving archival materials to Washington-on-the-Brazos. Nevertheless, he had become the state’s Governor, and Austin had begrudgingly accepted him. That acceptance was made easier with his pro-union stance toward the pending war.

Austin and its surrounding counties were, in 1861, the only place in Texas to reject secession as the solution.

But by Sam Houston’s day to make his oath, enough uncertainty had filled the room for his decision to remain a true mystery. He was a pro-union man, some argued, but his reasons were pragmatic ones. Governor Houston never expressed while in office an outward abhorrence of slavery or a fundamental disagreement with the idea of state sovereignty. He simply thought a war would be too long and costly, in money and lives, for the South to ever succeed. Maybe, many in attendance that day could reason, their beloved Governor had seen truth in his heart.

A diary account, left from his wife, indicates that Houston paced and contemplated virtually the entire night before. He was older now – more tempered in his decisions. Cautious, yet still indecisive. Sam Houston had been at war in one way or another almost his entire life.

He stepped to the podium, on March 16th, having made the decision for good just hours earlier, his wife by his side:

Fellow-Citizens, in the name of your rights and liberties, which I believe have been trampled upon, I refuse to take this oath. In the name of the nationality of Texas, which has been betrayed by the Convention, I refuse to take this oath. In the name of the Constitution of Texas, I refuse to take this oath. In the name of my own conscience and manhood, which this Convention would degrade by dragging me before it, to pander to the malice of my enemies, I refuse to take this oath. I deny the power of this Convention to speak for Texas….I protest….against all the acts and doings of this convention and I declare them null and void.

A silence. Houston climbed down from the podium with little awkward steps, aging in the action. Once lionized by these people, once made the hero of a state of frontiersman, adventurers – gunslingers and eccentric scholars alike. Once the embodiment of Texas.

A man from Louisiana who had traveled to Texas specifically for the convention recalled Houston’s demeanor as: “…cold with pity, as if to the gallows.”

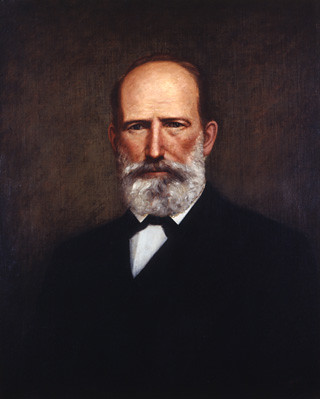

Other accounts suggest that before Sam Houston could even leave, riders had been dispatched to local Texas armaments. Somewhere in the building, Lieutenant Governor Edward Clark and a small group of conspirators stirred. Clark had anticipated this for some time, and all the various aspects of the contingency were already set in motion.

On the night of March 16th, Houston came to rest filled with uncertainty in the same way that the rest of his state had. Two messages arrived. The first from his Lieutenant Governor, Edward Clark. No surprise. The second from an Union Colonel, on behalf of Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln’s message said, in so many words, that if Houston desired, they would burn Austin to the ground.

And again, Sam Houston paced and contemplated.

End of Part 1.

.

Want more RoA? Be our friend on Facebook. Add our RSS feed! [what’s that?]. Start your morning with Republic of Austin in your InBox. Or read us 24-7 on Twitter!

Related posts:

- With Twilight fever rising, RoA challenges Gov Rick Perry to come out for Team Jacob. Looking at the facts and rumors around Texas Governor Rick...

Related posts brought to you by Yet Another Related Posts Plugin.