What happened to the Tonkawans, Austin’s original residents?

When I was a young kid — in pre-school and such, we used to have little Thanksgiving festivities to celebrate the holiday. You know: we’d do cut outs of our hands and color them and they were somehow supposed to look like turkeys, we’d sing songs based on the sounds they make (gobble gobble gobble!) and so on. We even had a Thanksgiving feast that involved 50% of the class dressing up in pilgrim costumes and 50% of the class dressing up in Native American costumes and eating together. Despite the fact that Native Americans and Pilgrims very likely had little to do with one another in terms of Thanksgiving history, this is probably one of my favorite early childhood memories.

Now, years later, I look back and think about how terribly offensive that might be to dress up a bunch of four-year-olds as Native Americans and imply that they got along with a group of people who stole from and killed them for a couple of centuries, but there is also a natural curiosity that develops from the same thing. While I can’t envision the Kickapoo people sitting down in their suburban ranch, throwing down a Butterball and catching some Detroit Lions licensed football, every Thanksgiving I do think about the way in which Native Americans lived and live as opposed to how we do. I think about how the absurdity of an American holiday that’s primary goal is basically to consume as much food as humanly possible in 24-hours with brief periods of hibernation in between is both hilarious and romantic at the same time.

In my first week here with Republic of Austin, the post that proceeded mine was an excellent piece by Ari Guerrero about what we could learn on sustainability from Austin’s most local Native American tribe: the Tonkawa. Immediately, I thought to myself, “Self, learn about the Tonkawa. Then share!”

Well folks, here is my Thanksgiving gift to you.

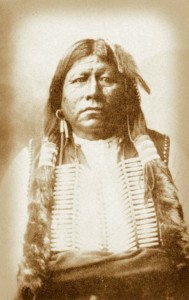

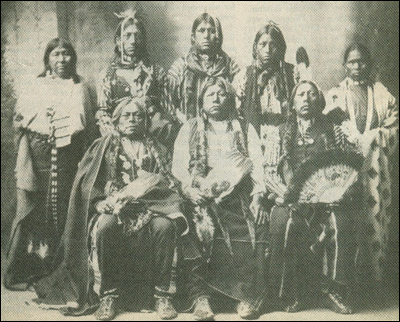

Despite popular belief, the Tonkawa people actually originated in Oklahoma, not Texas, in the early 17th century. They believed themselves to be literal descendants of wolves, and thus required to hunt and gather for their food. This frustrated white settlers who wished to incorporate them into their ways of farming. Their connection with the wolf was not universal, however. They also referred to themselves as “tickawantic” which translates to “the most human people”.

Often friendly with white settlers, there are several instances in history in which the Tonkawa allied themselves with white Texans, often for their own benefit as well as that of the whites. Tonkawa were frequently the subject of aggression by the Comanche for instance, and their allegiance to the Texas Rangers assisted both white Texans in moving other Native American tribes, and the Tonkawa in protecting their own lands. This allegiance stretched so far as the Civil War, which would also lead to much of the Tonkawan decimation.

Aligning with the Confederacy during the Civil War, Tonkawa went up against several Union armaments without the help of their fellow Texans, and were beat very badly. During the Civil War, Union soldiers killed over a third of living Tonkawans in perhaps one of the bloodiest untold stories of the conflict. The bad news did not stop. The constant warfare, discrimination and eventual forced relocation by their former Texas friends led them to the brink of extinction. By the 1950s, less than 100 Tonkawa remained.

The present day Tonkawa have benefited some from “angloification,” and now see their tribal numbers at about 600. But the cost of that slide into subservient “whiteness” has been a near total decimation of their heritage. Instead of being hunters and gatherers, Tonkawa people are now unfortunately Oklahoman reservation merchants, the “Indian Casino” stereotype that you read about in bad magazines or radio programs.

I don’t think it’s apparent to us when we’re kids or maybe even older, that Thanksgiving is about appreciation and celebration of our charity to one another. We are all somewhat connected to this idea: That each of us has others who are responsible for who we are — that we most certainly could not have made it here, wherever “here” is, on our own. Native Americans are no different. They made it possible for our ancestors, who made this possible for us. We’ve almost never celebrated them appropriately, nor the sacrifices that people like the Tonkawa have endured for our sake, usually without a choice. This Thanksgiving, I’ll be thankful not only for what has been given, but what we’ve taken. I hope you do the same.

Now enjoy your turkey, ya filthy animals.

No related posts.

Related posts brought to you by Yet Another Related Posts Plugin.

interesting slice of perspective on thanksgiving…the killing of native americans is probably the most undertold story in american history.

I never understood the thanksgiving dress-up when I was younger, probably since I moved to the U.S. at age 8…

Are we sure the Tonkawans originated in Oklahoma? I thought it was the other way around: originally from the Balcones Escarpment and from there forcibly moved to Oklahoma as were lots of other tribes in the Trail of Tears, etc.

Hey Kerri,

Scholarship for a (very) long time seemed to suggest that Tonkawans were from Central Texas, but recent research by Native American historians — within the last 15-20 years or so, and information put forth by some folks with vested interest in Oklahoma suggest that they actually originated in Oklahoma.

We can’t, of course, ever really be “sure” of such things, just a best guess, but the latest opinion from an academic historical perspective is the Tonkawans were in Oklahoma before they were in Texas.

Thanks for reading!